Sociology

This piece was originally featured on Research Matters.

After a three year hiatus, the Memory Studies Group at The New School for Social Research regrouped and reemerged in March 2020. Less than a week after their first event, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the world — and halted many of their plans.

Now, just over a year later, the revived group will hold their first conference this April: “Suspended Present: Downloading the Past and Gaming the Future in a Time of Pandemic.” Research Matters spoke about with group members and leaders about the group’s history, its current projects, and its future.

The History of the Memory Studies Group

“The idea for the Memory Studies Group came up…in Krakow, Poland, during the Democracy & Diversity Summer Institute in 2007,” recounts faculty advisor Elzbieta Matynia, Professor of Sociology and Director of the Transregional Center for Democratic Studies (TCDS), which conducts the annual summer study intensive. She had just taught her first class in collective memory. As her students walked through Kazimierz, Krakow’s historic Jewish quarter, they noticed a pattern: “…beautifully renovated buildings, various institutions, cafes, restaurants, and the streets were all named for its Jewish past. The only thing missing was the Jewish people, who had been taken to the Nazi concentration camps, and murdered there. It became visible to us then, this uncanny presence of absence.”

This experience sparked an interest in memory among Institute students, who became the founding cohort of an independent Memory Studies Group: Amy Sodaro, Sociology PhD 2011; Lindsey Freeman, Sociology & Historical Studies PhD 2013; Yifat Gutman, Sociology PhD 2012; Alin Coman, Psychology PhD 2010, and Adam Brown, Psychology PhD 2008 and now Associate Professor of Psychology at NSSR. They organized a conference in the group’s first year, where scholars discussed questions like “Which past is official? What is it that we remember? How do we forget when we are not allowed to remember? How do groups remember their history when their memory is being repressed, and what is happening to people whose very existence is repressed from memory?”

When Malkhaz Toria, group coordinator and a Sociology MA student, came to NSSR as a Fulbright scholar in 2011, the Memory Studies Group became an intellectual home for him. “That inspired me to establish a similar sort of group at my home university, Ilia State University in Tbilisi, Georgia,” he says; he also heads that university’s Memory Center.

Upon his return to NSSR in 2019, Toria was instrumental in reviving the group, which had gone on a brief hiatus. Now part of TCDS, the group has new core members of Franzi König-Paratore, Sociology PhD student; Elisabeta “Lala” Pop, Politics PhD student; Malgorzata Bakalarz Duverger, sociologist, art historian, and Sociology PhD 2017; Chang Liu, Sociology MA student; and Karolina Koziura, Sociology and Historical studies PhD student.

“Our goal is also to have some continuity of the transnational and transdisciplinary projects and exchange that Sodaro and Freeman envisioned and implemented when they were steering the group,” König-Paratore says. “My hope is that the group continues to connect past and present members. I personally hope that we open up the group more for professionals or cultural workers outside of academia.”

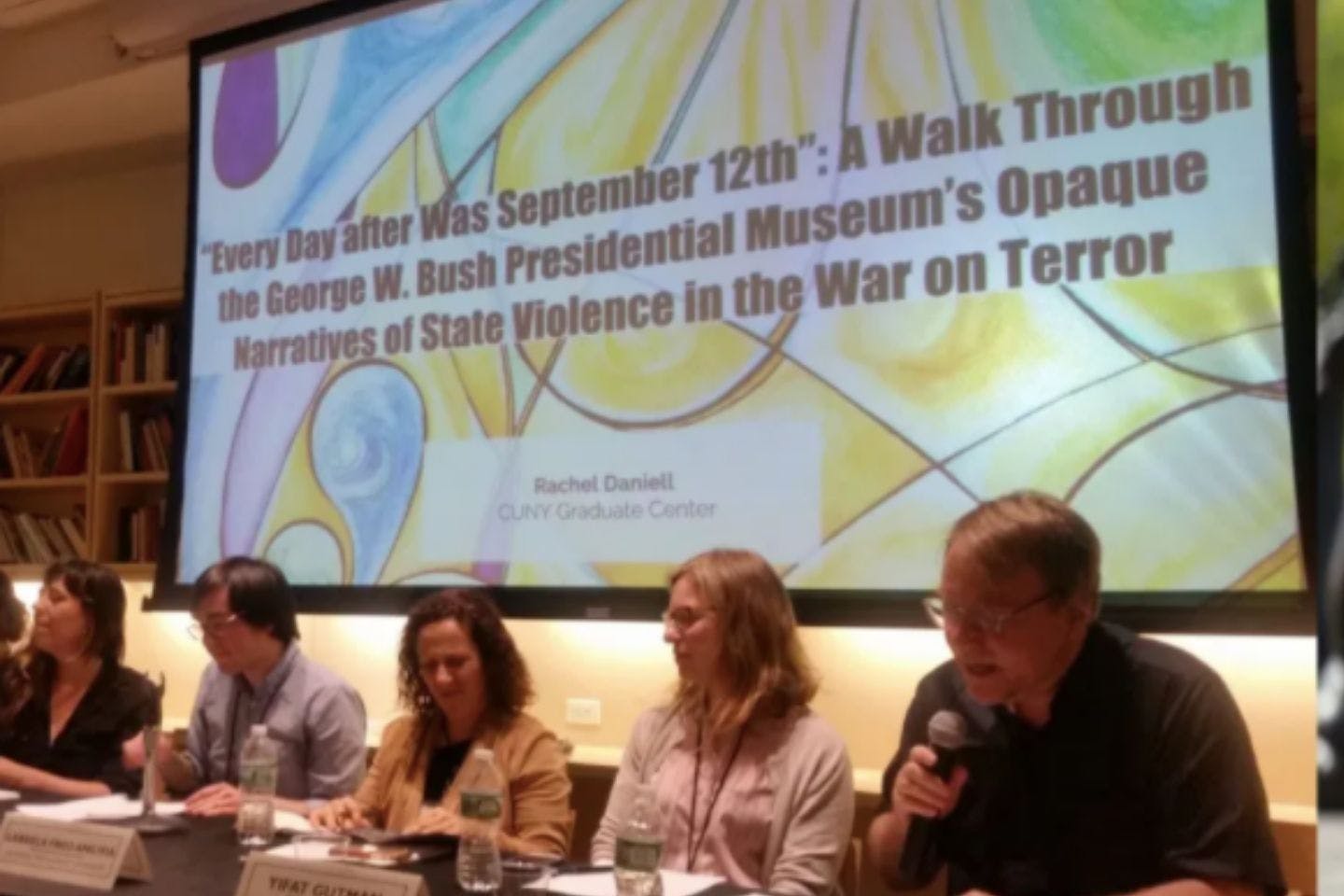

The revived group’s first and only in-person event was a March 2020 book launch for Museums and Sites of Persuasion, which was edited Sodaro and Joyce Apsel, and includes work by Alexandra Délano Alonso, Associate Professor and Chair of Global Studies at the School of Public Engagement, Toria, and many others. Since then, the group has held several online lectures and webinars and on discourses within the field, from a look at revisionist narratives in Russia to an examination of how Frida Wunderlich — the first female economist at NSSR and a founding member of the University in Exile — is remembered.

Memory Studies: A Transdisciplinary Field

Memory Studies spans disciplines in the social sciences and the humanities to explore the ways collective memory is constructed, experienced, repressed, and rebuilt. “The complex field of memory studies employs whole repertoire of approaches from different disciplines including comparative literature, history, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and politics, among other areas, to address the multifaceted phenomena of both individual and collective memories ,” Toria says. Matynia describes the field as “transdisciplinary.”

For example, Silvana Alvarez Basto, Liberal Studies MA student, looks at the intersections between politicization of art, history, and visual representations of memory in her home country of Colombia. “The topic of memory is very popular right now, since in 2016 the government ended an armed conflict with the FARC,” she says. Her research focuses on the construction of Simón Bolívar’s image as a national symbol across Latin America, in groups like the FARC and beyond. “I’m interested in how his face has become a guiding locus or a symbol for these movements,” Alvarez Basto explains. While her work has primarily dealt with 19th century portraits of Bolívar, she has recently begun looking at the ways “new technologies modify our relationship with canonical images and with the Western tradition of painted portraits.”

Toria works on the role of memory construction in authoritarian regimes and their aftermaths. Collective memory, he explains, does not come into existence organically. “It’s controlled and dependent on political conjunctures…Across the globe, if you have a totalitarian government, they are more keen to control how you remember.” His research looks at citizens in countries that were part of the Soviet Union. “Ukrainians, Georgians, and Estonians have different pictures of the past and past relationships with Russia. That’s why these clashes in questions of the past happen; it is quite a universal mechanism.”

“My first encounter with the Memory Studies Group at the New School was in 2009 when I was pursuing an MA degree. Through the [group] and TCDS I became connected with the interdisciplinary research and networks of the field and it greatly influenced my own MA thesis work,” Pop explains. “Now [that] I’m back at NSSR, I’m excited to be part of the team of graduate students continuing the group’s work and re-launching its activities.”

Memory Studies Today

Memory Studies takes on particular relevance in periods of upheaval, when democracies come into existence or are threatened, when social movements gain power, or when societies experience unprecedented change — periods like today.

Matynia points to several factors that make the current moment crucial for the field. Many countries have experienced what Matynia calls “de-democratization,” under the influence of dictators and “would-be dictators” who weaponize collective memory. “Politics of history and politics of memory became a part of the playbook of many dictators and aspiring dictators,” she explains.

Additionally, social movements have begun exposing and dismantling parts of the past that had been manipulated or repressed out of collective memory. Think of activists taking down statues of Confederate leaders in the U.S, slaveholders in the U.K., and a conquistador in Colombia. “There’s this rippling where people want to ask, ‘what does it mean to memorialize these figures?’” Alvarez Basto says.

Memory Studies doesn’t just look at the past; the field is equally interested in the ways that people form collective memory now in preparation for the future. The massive shift in March 2020 into lockdown and onto Zoom inspired the group’s April 21 conference, “Suspended Present: Downloading the Past and Gaming the Future in a Time of Pandemic.” Speakers will include Marci Shore, Associate Professor of History at Yale University; Hana Cervinkova, Professor of Anthropology at Maynooth University; and Juliet Golden, Director of the Central Europe Center at Syracuse University.

Toria explains, “There’s a kind of eternal presence that feels never-ending. Our world is reduced to these small screens, where our lives are… We’ll cover multifaceted aspects of Memory Studies in this new light, the context of the pandemic, like problems of democracy, remembrance, the problem of forgetting, shifting senses of time and space, and new issues in memory discourse surrounding gender and race.”

“We call it memory studies, but so much of what we think we are rooted in and call our past actually projects into the future,” Matynia adds. “So which past will we download as we moveout of today’s situation, and draw upon as a springboard for reinventing our intellectual lives, spiritual lives, and social lives?”